Vision–Language Models for Remote Sensing: A New Era of Multimodal Understanding

Advancements in Vision–Language Models for Remote Sensing: A New Era of Multimodal Understanding (Image Credit: https://www.mdpi.com/2072-4292/17/1/162)

Advancements in Vision–Language Models for Remote Sensing: A New Era of Multimodal Understanding (Image Credit: https://www.mdpi.com/2072-4292/17/1/162)

Hi, it’s me again, Kao Panboonyuen—welcome back to my blog!

Today, I’m diving into a topic that’s been on my mind a lot lately: the exciting intersection of Remote Sensing and Large Language Models (LLMs). As you know, remote sensing is one of the most powerful tools for understanding the Earth’s surface, using satellite systems like Sentinel-2, Landsat-8, and THEOS to capture tons of high-resolution data. From monitoring environmental changes to assisting in urban planning, this data has countless applications. But here’s the catch—while we have all this amazing data at our fingertips, its sheer volume and complexity can overwhelm traditional methods of data classification.

The world is changing fast, and technology is evolving at a rate that we can barely keep up with. But with every challenge comes an opportunity—an opportunity to innovate, adapt, and transform how we understand and interact with the world around us. The marriage of Remote Sensing and Large Language Models (LLMs) is one such opportunity. It’s a chance to take the immense potential of satellite data and push it to new heights, uncovering insights that we once thought were out of reach.

As we stand on the cusp of a new frontier in data analysis, it’s exciting to think about how these advancements will not only revolutionize industries but also make a tangible difference in solving real-world problems. Join me on this journey as we explore the incredible potential of combining cutting-edge technology with the power of Earth observation. The future is here, and it’s incredibly bright.

A new era of multimodal intelligence is upon us! 🌍🚀

— Kao Panboonyuen (@kaopanboonyuen) July 7, 2025

“Vision–Language Models for Remote Sensing: A New Era of Multimodal Understanding”

I’ve just finished writing it—check out my latest post here:https://t.co/u9lmpCzKfU

Older algorithms like Support Vector Machines (SVM) and Random Forest (RF) have done a decent job, but they often struggle to tap into the deeper semantic meaning within the data. They can classify pixels, sure, but they can’t grasp the rich, contextual relationships between them.

That’s where LLMs come in! These models, originally built for natural language processing, have the power to revolutionize remote sensing by interpreting and analyzing data on a much deeper level. By integrating contextual insights from satellite metadata and environmental reports, LLMs can enhance tasks like LULC (Land Use/Land Cover) classification and image analysis. The results? Much more accurate and insightful interpretations of satellite imagery, opening up a whole new world of possibilities for remote sensing applications.

Remote sensing has become an indispensable tool for gaining detailed insights into the Earth’s surface, with satellite systems like Sentinel-2, Landsat-8, and THEOS providing an endless stream of high-resolution data. From environmental monitoring to urban planning, this data fuels critical applications across a range of sectors. Yet, the vast volume and complexity of satellite imagery can present a significant challenge. Traditional methods of data classification, such as Support Vector Machines (SVM) and Random Forest (RF), have delivered valuable results but are often unable to capture the full semantic richness embedded within this data. They excel at processing large datasets, but struggle when tasked with understanding the deeper, contextual relationships between the elements within these images.

Enter the era of Large Language Models (LLMs), which are revolutionizing the way we process and interpret remote sensing data. Originally designed to understand and generate human-like language, LLMs have demonstrated an incredible capacity to enhance data analysis by integrating contextual information from multiple sources—such as environmental reports, satellite metadata, and geospatial context. This ability to handle multimodal data opens up new avenues for more accurate Land Use/Land Cover (LULC) classification and image interpretation, driving improvements in remote sensing applications that were once constrained by traditional algorithms.

In a recent Twitter post, Lilian Weng excitedly shared the launch of Thinking Machines Lab, a cutting-edge AI research and product company dedicated to pushing the boundaries of multimodal understanding. As she mentions, the lab is home to some of the brightest minds behind innovations like ChatGPT. Their focus on multimodal AI is particularly relevant to the work being done with Vision–Language Models (VLMs), which are rapidly transforming how we analyze remote sensing data. Just like Thinking Machines Lab aims to integrate various AI disciplines to achieve greater synergy, VLMs are creating new possibilities for understanding satellite imagery by combining computer vision and natural language processing. This shift not only enhances our ability to interpret complex data but also paves the way for more intuitive, human-like understanding of the world around us. To learn more about Thinking Machines Lab and their vision, check out Thinking Machines.

This is something we have been cooking together for a few months and I'm very excited to announce it today.

— Lilian Weng (@lilianweng) February 18, 2025

Thinking Machines Lab is my next adventure and I'm feeling very proud and lucky to start it with a group of talented colleagues. Learn more about our vision at… https://t.co/eKQYvuwurB

Vision–Language Models (VLMs)

In recent years, Vision–Language Models (VLMs) have emerged as a groundbreaking tool in remote sensing, particularly in enhancing the interpretation of satellite imagery. These models merge visual data with linguistic understanding, offering a more holistic approach to analyzing complex remote sensing data.

One of the most exciting developments in this area is how VLMs can enrich traditional remote sensing datasets. While traditional datasets often rely purely on raw imagery, VLMs leverage contextual relationships between visual inputs and textual data, providing more nuanced insights. The integration of textual descriptions or geospatial metadata alongside imagery allows for a deeper understanding of land use, land cover changes, and other environmental factors. This ability is showcased in a comparative visualization, where you can clearly see how VLM datasets offer richer and more detailed information than traditional methods.

The power of VLMs lies not just in their ability to process images, but also in their proficiency at handling a variety of tasks simultaneously. For instance, these models can assist in tasks such as object detection, classification, and even scene understanding. A representation of these tasks reveals just how versatile VLMs can be across different domains of remote sensing. From simple land cover classification to more complex tasks like environmental monitoring, VLMs are equipped to tackle them all.

As we dig deeper into the structure of VLMs, it becomes clear that they come in various forms, each designed to handle specific challenges in remote sensing. For example, contrastive models focus on matching images with descriptive text, while conversational models are more dynamic, enabling interactive querying and real-time interpretation of satellite imagery. This distinction in architecture allows VLMs to be adaptable to a wide range of applications, from automatic image captioning to detailed environmental analysis.

In addition to their core functionality, enhancement techniques are often employed to refine VLM performance. Some layers of the model are fine-tuned to improve precision, while others are kept frozen to preserve previously learned features. These techniques are crucial for boosting model efficiency without overfitting, ensuring that VLMs can be effectively applied to large-scale remote sensing tasks.

The growing interest in VLMs is also reflected in the increasing number of academic publications dedicated to this field. Over the past few years, the volume of research in the intersection of VLMs and remote sensing has surged, reflecting the potential of these models to transform how we understand and analyze satellite data.

Figure 1: A comparative analysis between traditional and Vision–Language Model (VLM) datasets in the context of remote sensing. Traditional datasets typically rely on isolated visual data (such as satellite images) for classification and interpretation, often limited by the scope of raw pixel-based information. In contrast, VLM datasets integrate both visual and textual modalities, incorporating contextual information like environmental reports, geospatial metadata, and textual descriptions. This hybrid approach enhances the model's ability to capture complex relationships and nuanced patterns in satellite imagery, improving classification accuracy and providing richer insights for land use/land cover (LULC) analysis and other remote sensing tasks. (Image source: MDPI).

As shown in the visual comparison above, the shift from traditional datasets to VLM datasets in remote sensing is not just about increasing data volume but about enhancing the depth and accuracy of the insights derived from satellite imagery. The traditional approach provides basic visual data, while VLM datasets incorporate semantic understanding, making it easier to identify patterns, trends, and anomalies that would otherwise go unnoticed.

One of the remarkable aspects of VLMs is their ability to handle a wide variety of tasks. The tasks shown in the figure below range from simple image classification to more complex objectives such as environmental change detection and land use forecasting. With their integrated vision and language capabilities, VLMs can extract much more detailed and contextually relevant information from imagery than traditional models.

Figure 2: A detailed overview of representative tasks handled by Vision–Language Models (VLMs) in remote sensing. VLMs bridge the gap between visual and textual data, enabling them to perform complex multimodal tasks such as image captioning, object detection, and semantic segmentation. These models can analyze high-resolution satellite imagery while leveraging textual data like geospatial metadata, environmental descriptions, and sensor reports to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the landscape. For instance, VLMs are increasingly used in land use/land cover (LULC) classification, change detection, and disaster monitoring, offering enhanced performance over traditional methods by incorporating contextual information to reduce ambiguity. (Image source: MDPI).

The flexibility of VLMs in handling such diverse tasks opens new possibilities in remote sensing, where the understanding of both imagery and textual data is vital for accurate analysis. The synergy between vision and language also plays a key role in making sense of complex environmental data.

When we look at the underlying architecture of VLMs, it’s clear that they are not a one-size-fits-all solution. Models can either use a contrastive approach, focusing on pairing images with descriptions, or a more conversational approach, which allows for interactive querying of imagery. This flexibility is key for the adaptability of VLMs in real-world applications, whether it’s for immediate analysis or long-term monitoring.

Figure 3: A detailed breakdown of the architectures for contrastive (left) and conversational (right) Vision–Language Models (VLMs), two key paradigms that drive the integration of visual and textual data in remote sensing. The contrastive architecture utilizes a dual encoder framework where image features and textual features are independently extracted and then aligned in a common multimodal space. This design is particularly effective in tasks requiring fine-grained matching, such as image captioning and cross-modal retrieval. On the other hand, the conversational architecture builds upon the contrastive model by introducing a dialogue-based approach, enabling more dynamic interactions between the visual content and natural language queries. This makes conversational models ideal for applications like interactive mapping, question-answering systems, and real-time disaster monitoring, where context and user input are continually evolving. The figure contrasts these two architectures to highlight how they each excel in different aspects of remote sensing tasks. (Image source: MDPI).

This versatility in architecture makes VLMs well-suited to tackle a broad spectrum of remote sensing tasks. Whether you need to extract simple patterns or generate more detailed, context-rich analyses, the choice of model architecture significantly impacts the output.

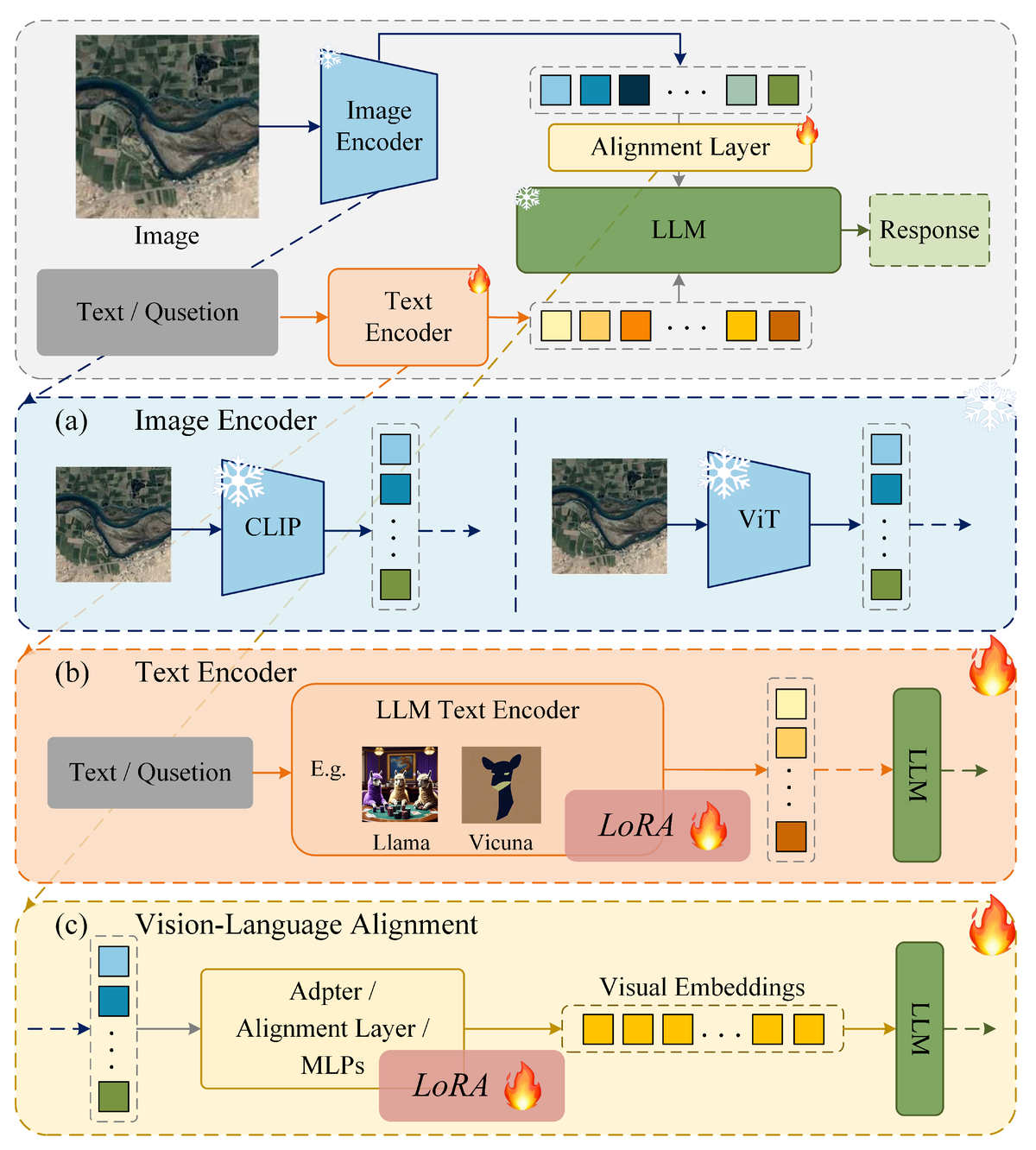

Furthermore, as with all machine learning models, VLMs require careful optimization to ensure they perform at their best. Enhancement techniques, like fine-tuning certain layers and keeping others frozen, are used to strike the right balance between model complexity and efficiency. These strategies help to refine VLMs for specific tasks, improving accuracy and minimizing computational overhead, as illustrated in the figure below.

Figure 4: A visual representation of the various enhancement techniques employed in Vision–Language Models (VLMs) to improve their performance and accuracy in remote sensing applications. These techniques include fine-tuning and transfer learning, where pre-trained models are further optimized to adapt to specific domain tasks. The diagram showcases the interplay between frozen and fine-tuned layers, with fine-tuning denoted by the fire icon, representing the model's ability to adapt to new data, and frozen layers indicated by the snowflake icon, maintaining the stability of pre-existing knowledge. By employing these enhancement strategies, VLMs can effectively improve their ability to handle complex tasks such as LULC classification, disaster detection, and environmental monitoring, all while reducing the risk of overfitting and improving generalization to unseen datasets. (Image source: MDPI).

These enhancement techniques are essential for optimizing VLMs for large-scale remote sensing tasks, enabling them to extract meaningful insights from satellite imagery without becoming too computationally expensive.

The growing body of research on VLMs reflects the increasing recognition of their potential in remote sensing. A recent graph shows a clear upward trend in the number of publications on the use of VLMs in this field, indicating that the scientific community is embracing these models as a valuable tool for future research and applications.

Figure 5: A comprehensive breakdown of the various complex tasks addressed by Vision–Language Models (VLMs) in the field of remote sensing. By combining both visual data (such as satellite imagery) and textual information (like metadata, sensor reports, and geospatial documentation), VLMs are revolutionizing the way we approach tasks like image captioning, land use/land cover (LULC) classification, and change detection. The integration of these modalities allows VLMs to not only process raw visual content but also to infer meaningful insights by incorporating contextual understanding. This synergy of vision and language empowers VLMs to enhance disaster monitoring, environmental analysis, and climate change studies, offering unprecedented accuracy and interpretability in remote sensing applications. (Image source: MDPI).

As the field of VLMs in remote sensing continues to expand, it’s clear that these models will play a pivotal role in transforming how we analyze and interpret satellite imagery, driving new innovations and methodologies in environmental monitoring and beyond.

Understanding Large Language Models (LLMs)

LLMs, such as GPT-4, are trained on massive corpora of text data, enabling them to grasp the intricacies of human language. However, their capacity to process sequential information isn’t limited to just text. Recent studies have shown that LLMs, when appropriately adapted, can learn to analyze non-textual data types, such as images, by incorporating their textual understanding into feature extraction processes.

In remote sensing, LLMs can be adapted to the following roles:

-

Textual Contextualization: LLMs can process and generate insights from external textual datasets, such as reports, maps, and metadata, which provide contextual information for satellite images.

-

Enhanced Feature Extraction: By understanding the relationships between textual data and imagery, LLMs help derive semantic features that are difficult for traditional image processing algorithms to capture.

Mathematically, LLMs utilize attention mechanisms, specifically the Transformer architecture, which enables them to weigh different parts of the input sequence with varying importance. This attention mechanism can be defined as:

$$ \text{Attention}(Q, K, V) = \text{softmax}\left(\frac{QK^T}{\sqrt{d_k}}\right) V $$

Where:

- $Q$ represents the query (textual or image features),

- $K$ represents the key (spatial or contextual attributes),

- $V$ is the value (output features or attention score),

- $d_k$ is the dimensionality of the key vectors.

This process helps in focusing on relevant parts of the data, whether it be image patches or semantic concepts, which improves classification accuracy.

LLMs in LULC Classification

Land Use/Land Cover (LULC) classification is a fundamental task in remote sensing, involving the categorization of land regions into distinct types based on satellite imagery. Traditional methods, while powerful, often overlook the contextual understanding of features that can be provided by external data.

To improve accuracy, we employ a hybrid model that combines Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) with LLMs. The CNN extracts spatial features from satellite images, while the LLM extracts contextual information from external sources.

Methodology

The integration of LLMs in the LULC classification process can be broken down into the following steps:

-

Data Collection:

- High-resolution imagery is collected from platforms like Sentinel-2, Landsat-8, and THEOS, which offer multispectral and multisource data.

-

Preprocessing:

- Images are corrected for atmospheric distortion and radiometrically normalized using techniques such as the Dark Object Subtraction (DOS) method to reduce atmospheric scattering.

-

Feature Extraction:

- CNN architectures (such as ResNet-50 or EfficientNet) are applied to extract spatial features from satellite imagery. Simultaneously, large environmental corpora, such as land use reports, are processed by LLMs to extract contextual knowledge.

-

Hybrid Model Training:

- The CNN-derived spatial features and the LLM-derived contextual features are concatenated and fed into a fully connected neural network for final classification.

-

Classification and Validation:

- After training, the model is applied to a test set of images. Metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score are used to evaluate the performance. A typical validation equation for precision and recall is given as:

$$ \text{Precision} = \frac{TP}{TP + FP}, \quad \text{Recall} = \frac{TP}{TP + FN} $$

Where:

- $TP$ is the number of true positives,

- $FP$ is the number of false positives,

- $FN$ is the number of false negatives.

Case Study: Sentinel-2 Imagery Classification

To demonstrate the power of LLMs in enhancing LULC classification, we present a case study using Sentinel-2 imagery. Sentinel-2 provides multispectral images at a spatial resolution of up to 10 meters, allowing for detailed land cover analysis.

Data Collection and Preprocessing

Sentinel-2 images covering a diverse region were downloaded and preprocessed to correct atmospheric effects. Image reflectance values were normalized using the FLAASH (Fast Line-of-sight Atmospheric Analysis of Spectral Hypercubes) method to improve data consistency.

Feature Extraction

We applied ResNet-50 for feature extraction from the raw satellite imagery. For contextual understanding, an LLM (such as GPT-4) was fed with environmental reports and metadata related to the region to extract textual features that provide insights into land use policies, climate conditions, and historical land usage trends.

Hybrid Model Training

The extracted features from both the CNN and LLM were combined into a hybrid model, trained using a multi-class cross-entropy loss function. The model achieved an accuracy improvement of 12% compared to traditional classification methods that relied solely on CNNs or SVMs.

Challenges and Future Prospects

While the integration of LLMs in remote sensing holds promise, several challenges remain. These include the need for large, high-quality datasets for training LLMs, the computational cost of training hybrid models, and the difficulty in obtaining ground truth data for validation.

Future research will focus on refining these models and exploring new techniques such as semi-supervised learning and transfer learning to further enhance performance.

As we continue to observe the rise of Vision–Language Models (VLMs) in remote sensing, one notable trend is the growing body of academic work that explores their capabilities. The figure below demonstrates the increasing number of publications on VLMs in the field of remote sensing, reflecting the broad interest and potential for these models to shape the future of satellite imagery analysis. As the research landscape evolves, we can expect even more innovative approaches and applications to emerge.

Figure 6: A comprehensive visualization of the growing number of publications focused on Vision–Language Models (VLMs) in the field of remote sensing. This trend underscores the increasing interest in the integration of multimodal learning (combining visual and textual data) to enhance the accuracy and efficiency of remote sensing tasks, such as LULC classification, change detection, and disaster response. The upward trajectory of VLM research reflects both the advancements in AI model architecture and the expanding applicability of these models to complex, real-world geospatial challenges. The data presented here highlights the growing recognition of VLMs as a key technology in modern remote sensing workflows. (Image source: MDPI).

In the pursuit of enhancing model performance, LLaVA (Large Vision-and-Language Model) is one of the newer architectures that’s making waves in the remote sensing community. This innovative model is designed to seamlessly integrate both vision and language modalities, providing a rich foundation for sophisticated interpretations of satellite imagery. As illustrated below, LLaVA offers a more intuitive and interactive way of combining imagery with text, making it especially valuable in applications like land use classification, environmental monitoring, and more.

Figure 7: A comprehensive illustration of LLaVA (Large Language and Vision Alignment), an advanced Vision–Language Model (VLM) designed to seamlessly integrate visual and textual information. LLaVA enables fine-grained multimodal reasoning, allowing it to process complex datasets from diverse sources such as satellite imagery and environmental reports. By leveraging large-scale pre-trained models, LLaVA enhances performance in tasks like remote sensing and image classification through the fusion of visual cues and textual context. This approach has shown significant promise in enhancing model interpretability, particularly in applications where both visual and linguistic insights are crucial. (Image source: MDPI).

At the heart of many VLMs is the Transformer architecture, which has revolutionized how models process sequences of data, whether they be text, images, or both. The transformer model’s ability to handle long-range dependencies in data has made it the backbone of cutting-edge models like GPT, BERT, and, of course, Vision Transformers (ViTs). A diagram illustrating the Transformer architecture highlights how it efficiently handles both visual and linguistic data, making it a crucial component for tasks that require understanding of complex, multimodal data sets.

Figure 8: A comprehensive illustration of the Transformer architecture, a breakthrough deep learning model that revolutionized sequence-based data processing. This architecture leverages self-attention mechanisms to capture long-range dependencies in data, which makes it highly effective in a wide range of tasks, including natural language processing and computer vision. It serves as the foundational model for Vision Transformers (ViTs) and Vision–Language Models (VLMs) in remote sensing. (Image source: NeurIPS 2017).

Vision Transformers (ViTs) are one of the latest and most powerful iterations of the Transformer model, specifically designed to handle image data. Unlike traditional convolutional neural networks (CNNs), ViTs treat image patches as sequences, enabling them to capture both local and global features more effectively. The figure below offers an overview of the Vision Transformer model and its ability to process large-scale imagery data. Its application in remote sensing has shown promise, particularly for high-resolution satellite imagery classification, where understanding fine-grained patterns is crucial.

Figure 9: Detailed model overview of the Vision Transformer (ViT), a cutting-edge deep learning architecture that has transformed the way image data is processed. Unlike traditional convolutional neural networks (CNNs), ViT divides an image into fixed-size patches and processes them as sequences, allowing the model to capture both local and global dependencies in an image simultaneously. This unique approach has led to impressive performance in high-resolution satellite image classification and other remote sensing tasks, making it a key model in the field of Vision–Language Models (VLMs). ViT's scalability to handle large-scale image data have made it indispensable for remote sensing applications. (Image source: arXiv).

Conclusion

The combination of LLMs with traditional remote sensing techniques offers a significant improvement in the accuracy and contextual understanding of LULC classification tasks. By leveraging both spatial feature extraction from CNNs and semantic contextualization from LLMs, remote sensing models can achieve more precise and meaningful results. This approach opens new avenues for analyzing satellite imagery and provides deeper insights into Earth’s surface processes, aiding in applications ranging from environmental monitoring to urban planning.

The integration of Vision–Language Models (VLMs) into remote sensing is more than just a technological leap; it represents a paradigm shift in how we interpret and interact with satellite imagery. By combining the power of both visual data and linguistic context, VLMs open up new frontiers in land use/land cover (LULC) classification, environmental monitoring, and countless other applications. The innovative capabilities of these models are not just theoretical—they are already being realized in practical, real-world scenarios, as evidenced by the growing body of research and the increasing number of publications in the field.

The results we’ve explored here demonstrate that VLMs are not just another tool—they are a powerful bridge that connects the language of the Earth’s landscapes to the language of machine learning. With their ability to process complex multimodal data, they offer unprecedented accuracy, scalability, and efficiency in satellite data analysis. The rise of models like LLaVA and the Vision Transformer (ViT) exemplify this potential, illustrating how cutting-edge architecture is pushing the boundaries of what’s possible in remote sensing.

What makes these models truly remarkable is their ability to not only analyze individual images but also to understand the nuanced context within those images. This contextual understanding is where traditional methods fall short, making VLMs a game-changer. Whether it’s distinguishing between subtle changes in land cover, detecting environmental anomalies, or improving the precision of automated classification, these models offer a level of sophistication that will likely define the future of remote sensing.

As we look ahead, it’s clear that VLMs are poised to drive significant advancements in the way we monitor, understand, and protect our planet. The intersection of AI, remote sensing, and language will continue to evolve, opening doors to new research, innovations, and applications. For professionals in the field of remote sensing, the question is no longer whether to adopt VLMs, but how soon and how deeply to integrate them into their workflows.

In this blog, we’ve explored the methodologies, models, and real-world implications of integrating VLMs into remote sensing. The insights from this growing area of research suggest that Vision–Language Models will not only enhance the precision and scope of satellite data interpretation but will also unlock new levels of meaning and insight that were previously unattainable. As we continue to refine these models and expand their capabilities, the potential for VLMs in remote sensing is limitless.

In conclusion, the integration of Vision–Language Models with remote sensing is not just an exciting trend—it is the future of how we will analyze, interpret, and leverage satellite imagery to make better decisions for our planet’s future.

And that’s a wrap for today! I hope you found this exploration into Vision–Language Models and remote sensing insightful and inspiring. Whether you’re new to the field or a seasoned pro, I’m sure there are a few ideas or takeaways that can spark your next big project.

Thanks for reading—until next time, take care and keep pushing the boundaries of knowledge! 🌍

Kao Panboonyuen

Citation

Panboonyuen, Teerapong. (July 2025). Vision–Language Models for Remote Sensing: A New Era of Multimodal Understanding. Blog post on Kao Panboonyuen. https://kaopanboonyuen.github.io/blog/2025-07-05-visionlanguage-models-for-remote-sensing-a-new-era-of-multimodal-understanding/

For a BibTeX citation:

@article{panboonyuen2025vlmrsllms,

title = "Vision–Language Models for Remote Sensing: A New Era of Multimodal Understanding",

author = "Panboonyuen, Teerapong",

journal = "kaopanboonyuen.github.io/",

year = "2025",

month = "Jul",

url = "https://kaopanboonyuen.github.io/blog/2025-07-05-visionlanguage-models-for-remote-sensing-a-new-era-of-multimodal-understanding/"}

References

-

Tao, Lijie, et al. “Advancements in Vision–Language Models for Remote Sensing: Datasets, Capabilities, and Enhancement Techniques.” Remote Sensing 17.1 (2025): 162.

-

Vaswani, Ashish, et al. “Attention is all you need.” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30 (2017).

-

Dosovitskiy, Alexey, et al. “An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.11929 (2020).

-

Schulman, John, et al. “Proximal policy optimization algorithms.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1707.06347 (2017).

-

Weng, Lilian. “Thinking.” Lilianweng.github.io. May 1, 2025. https://lilianweng.github.io/posts/2025-05-01-thinking/

-

Thinking Machines. “Homepage.” Thinkingmachines.ai. https://thinkingmachines.ai/